RBA governor Philip Lowe reads of mortgage stress with a ‘heavy heart’ but argues that the 10 consecutive rate hikes were necessary to avoid prolonged high inflation and higher unemployment.

The governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Dr Philip Lowe, has defended the central bank’s rapid rate hiking cycle between May 2022 and March 2023, arguing that not doing so would have resulted in more economic damage.

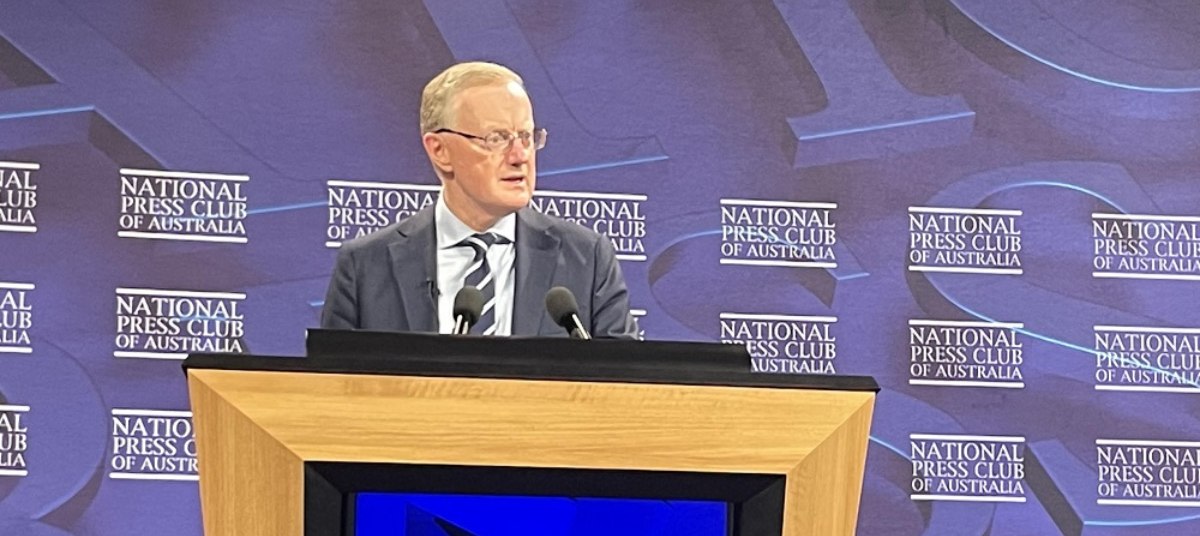

Addressing the National Press Club in Sydney on Wednesday (5 April) — the day following the Reserve Bank of Australia’s decision to hold the cash rate at 3.60 per cent for April — the RBA governor defended the bank’s decision to increase the cash rate by a cumulative 3.5 percentage points over 10 board meetings.

“The first increases [in the cash rate] were necessary to withdraw the support provided during the pandemic,” he said. “And then the more recent increases have been required to move monetary policy into restrictive territory to combat the highest rate of inflation experienced in Australia in more than 30 years.”

Mr Lowe argued that the alternative to the recent interest rate increases would have been “more persistent inflation and, ultimately, even higher interest rates and more unemployment”.

He added that while the “large increase over a short period” has been “difficult for many people” — and revealed that many Australians had been writing to him to outline the pressure they are facing as the cost of their mortgage increases — he suggested that the alternative would be much worse.

In response to a question from ABC regarding what information the central bank has from charities supporting families with the growing cost of living, Mr Lowe said that he will be meeting with a number of service providers “to hear their stories directly” in the coming month.

He continued: “Quite a few Australians write to me, telling me of the very difficult situation that they’re in and I read those letters with a heavy heart.

“But when I read them, I think: ‘What is the alternative?’

“If we didn’t put up interest rates, what’s going to happen? Inflation will stay high, interest rates will have to get higher later on and there’ll be more unemployment.

“So, at the individual level, it’s very difficult but this rise in interest rates has been necessary. And if we didn’t do it, then there’s more pain down the track. So it’s a hard message but it is the truth.”

Fixed-rate cliff actually a ‘ramp’: Lowe

The RBA governor was also asked by journalists about the fallout from the impending ‘mortgage cliff’, as hundreds of thousands of borrowers roll off their fixed-rate terms this year onto higher variable rates.

In response, Mr Lowe said he didn’t like the analogy of it being a “cliff”.

Mr Lowe explained: “This is not a cliff; it’s kind of a ‘ramp up’. I mean, a lot of people have already transitioned their fixed rate loans to variable rate loans and the banks tell us that people who’ve already transitioned are performing as well with their mortgages as the people who have variable rate loans.

“We’ve got to remember that many of these people who’ve had [fixed] rate loans for one/two/three years, have paid much, much, lower interest rates than the rest of the community for that time.”

Mr Lowe suggested that some of the borrowers who have been writing to him have said they have been saving money while their fixed rates have been low but conceded that others “are going to face a difficult adjustment”.

In his address to the National Press Council of Australia, Mr Lowe outlined that the 35 per cent of households with a mortgage either are, or will be, experiencing “a significant increase in their required payments”, adding that the predominance of variable-rate mortgages in Australia means that this is a more powerful transmission mechanism of monetary policy than in many other countries.

“Since interest rates started rising, the average mortgage rate that Australians pay has increased more quickly than average mortgage rates paid in other countries,” he revealed.

“This increase in mortgage rates has had a significant effect on household budgets and we anticipate that required mortgage payments will reach a new record high of almost 10 per cent of household disposable income by the end of next year.”

However, he said that borrowers have “known for some time they have to pay higher rates”.

“Most people are sensible … they’ve been planning for it [the rise in interest rates],” Mr Lowe said.

“It doesn’t make it easier, but they’ve been planning for it. And the banks tell us that they’re working very carefully with those customers that make the transition and there’s been no deterioration in the credit quality of those borrowers.”

As well as noting the pressures on mortgagors in a rising rate environment, Mr Lowe also highlighted that the rising cost of rents (which has been rising amid a dearth of rental supply and as investors work to meet higher mortgage repayments) was becoming a growing concern.

According to Mr Lowe, the financial counsellors that the RBA engages with as part of its liaison program have flagged that they’re getting increased calls from people saying they’re in financial stress.

“A lot of those calls, interestingly, are coming from people who rent,” he said.

“At least as many of them [than from mortgagor] ... and so rental stress is at least as big an issue, at the moment, as mortgage stress.”

During the course of the event, the RBA governor outlined that the central bank believed it was “way too early” to start talking about rate cuts, adding the bank does not expect its inflation target of 2–3 per cent to be hit until ‘mid 2025’.

[Related: The fixed-rate mortgage cliff and how brokers can help]